Eugenio Espinoza and the Device of the Cut

Nadja Rottner

To begin a discussion on the role of the cut in the geometric abstractions of Eugenio Espinoza, a key practitioner in Venezuelan art since the 1970s, we ought to point out the most obvious of facts first—namely, that a technique of scissoring is above all anchored in a dynamic between the hand and the eye.

1

The cut in postwar art functions as a space-forming device, limiting the ability of the pictorial to function illusionistically. It is impossible to discuss the cut in art and not consider the slashed monochrome canvases from the Concetto spaziale series by Argentine-Italian artist Lucio Fontana from the 1950s, executed with a knife. New York–based minimalist sculptor Carl Andre famously elaborated on the role of the cut as an instrument for acquiring spatial knowledge in 1966, observing that “Up to a certain time I was cutting into things. Then I realized that the thing I was cutting was the cut. Rather than cut into the material, I now use the material as the cut in space.” David Bourdon, “The Razed Sites of Carl Andre,” Artforum 5, no. 2 (October 1966): 17.

Espinoza’s approach to space forming by cutting is an extension of this historical legacy, but his is not a gesture of destruction, nor does he subscribe to a literalist definition of materiality in art in its embrace of chance, spontaneity, innate material behavior, and gestural activity by hand.

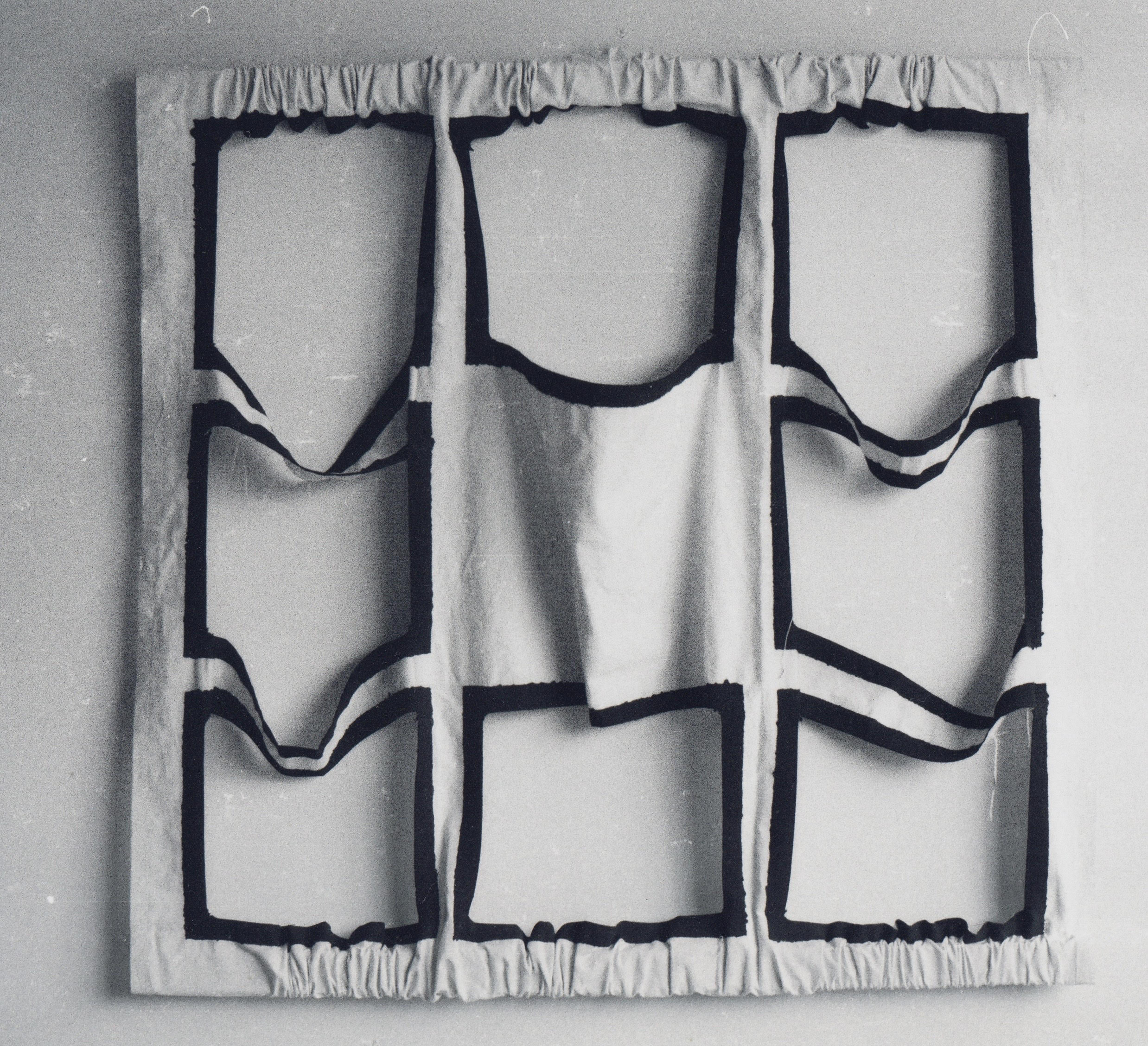

In hand-eye coordination, a surface cut from industrial fabric provides a background plane against which future pictorial inscription is defined. (Figure 1)

What is at issue in the popular twentieth-century paradigm of geometric abstraction is a freedom of experimentation with simple geometry (the square, the circle, the rectangle), color, gestural application, material, and texture choices, alongside an ordering of spatial relationships between various compositional parts—as well as an activation of the physical “reality” of surrounding space.

2

In the growing literature on Espinoza, the artist is repeatedly cited regarding his exposure to a wide range of twentieth-century traditions of geometric abstraction including French cubism, Dutch neoplasticism, Russian suprematism and constructivism, American minimalism, Italian arte povera, and Venezuelan optical and kinetic art. In one of his most recent interviews, in 2021 the artist says, “In art books, I saw the paintings of Piet Mondrian, and later the works of Gego, Jesús Rafael Soto, and Alejandro Otero. I also saw the grid everywhere, even in sociopolitical systems of control. When I first started to paint, I did not want to work with any form of representation. The inspiration I received from Venezuelan artists such as Gego, but also from those abroad including Lucio Fontana and Piero Manzoni, convinced me to choose the grid.” Madeline Murphy Turner, “Off the Grid: A Conversation with Eugenio Espinoza,” May 26, 2021, https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/571.

He also encounters white, modular minimalistic sculptures with black shapes in Luz y transformación, the second group show of the local Expansionismo group at the Ateneo de Caracas in October of 1967, with by Omar Carreño, Álvaro Sotillo, and Ruben Marquez. Phone interview with the artist, May 20, 2022. A discussion of the semiotic nature of each of these artwork references is beyond the scope of this essay.

Espinoza chooses unprimed canvas, a square or grid figure, painted black bands, the shaping of “empty” space, and gestural activity by hand left visible to the discerning eye as the key formal parameters of operation for his art of variation.

3

Black Square by Kazimir Malevich (1915) serves as a historical reference. Espinoza asserts that he “was very interested in what Malevich said about the square [and emptiness in art], that it was a perfect shape that contained everything.” “Calculated Disorder: Eugenio Espinoza in Conversation with René Morales,” Eugenio Espinoza: Unruly Supports (1970-1980), ed. Jésus Fuenmajor (Miami: Pérez Art Museum, 2015), 132.

Unprimed canvas and emptiness in abstraction have a place in Venezuelan art history. The early landscapes of Armando Reverón, between 1926 and 1934, rely predominantly on coarse unprimed canvas and burlap to invoke the local specificity of Macuto. Alejandro Otero’s seminal Pince et carré blanc (Brush and White Square) (1963) explores the effects of empty space by hanging an “empty” white, square picture frame on a white wall side by side with a brush, both covered in white enamel paint.

In Espinoza’s most recent series, titled Onceptuales (2022), the cut does double duty. It functions as a technique to bring figure into being, and it acts as a cutout, charging that which is absent with pictorial presence. (Figure 1) To take a case in point, Onceptual #3 is assembled from coarsely cut canvas bands with frayed edges, glued together, with painted black fronts and unprimed backs poking noticeably into the foreground. Pictorial depth—understood as the optical distance between the canvas cells and the painted lattice with three-inch-thick black acrylic bands—is at a minimum. From a side view, the grid of nine square cells showcases an irregular, undulating armature at a variable, impossible-to-measure depth of about seven inches. The bent canvases from this series transfigure the right-angle grid symbolic of the domain of abstract human thought (the precision and stability of the grid exists in this orthogonal purity only on the two-dimensional x and y axes of Cartesian geometry) into the changing z dimension of three-dimensional space. The gestural exertion of different kinds of physical pressure onto the painted figure leads to a signature stylistic look generally described by the artist and others as a distortion, deformation, or unhinging of the orderly, right-angle appearance of simple geometry.

Venezuelan art critic Lourdes Blanco turns to a canvas-as-body metaphor to capture the elusive physical appearance of these works, at odds with constructivist, optical, or kinetic approaches to geometric abstraction, as pseudo-organic entities that are “living media—torn, unraveled and swollen.” 4 Lourdes Blanco, “Recordando Sin Iras (Remembering Without Rancor),” Poliester 4, no. 14 (Winter 1995-1996): 10. A metaphor as a figure of speech describes an object or a person in a way that is not literally true by equating it or them to something else, a form of analogy. Art history offers up yet another semiotic explanation, one which does not rely on visual-surface similarity to capture the important role of gestural activity in Espinoza’s geometric abstractions. Mark-making in art features dripping lines, coarse patterns, textures of a thick horsehair brush, or the frayed cut left noticeable as a trace, visibly manifesting the physical presence of the artist in the act of making. The cut exemplifies the reciprocal interaction between the body and the world that is the condition of visual artmaking. It is caused by a moving body part, left standing as a sign, just like a footprint in snow is the direct indexical result of a person’s stepping in it. 5 See Rosalind Krauss’s landmark essay, “Notes on the Index: Seventies Art in America,” October 3 (Spring 1977): 68-81. One important feature of Espinoza’s employment of the cut is its capacity to sustain dual references to space occupancy as both a gestural and a perceptual task, albeit accomplished by different forms of semiotic reference.

Looking at Onceptual #3 from the front, the canvas offers up a surprise as the viewer approaches the artwork. (Figure 2)

The saggy and malleable three-by-three black lattice structure hosts three nesting squares in white acrylic on canvas that form a diagonal line from the lower left corner to the upper right-hand side. The joint absence of both wooden support stretcher and picture frame allows the cut to function as a plastic and pictorial tool for space creation. From a distance, we might experience a momentary confusion as to how many painted white cells are physically there versus how many fields are animated pictorially by the white wall behind. The cutouts in their concurrent positive and negative appearance in white jeopardize, albeit momentarily, firm figure-ground attribution.

This perceptual ambiguity triggers intellectual curiosity concerning the workings of how figure-ground attributions operate in perception. The cutout, in its joint role as either figure or ground, alludes to some basic (intuitively experienced) features of perceptual space such as positional relations of in front and behind, or figure and ground interaction on planar surfaces. An awareness of the mental construction of perception sets it, and the cut now operates as a rhetorical device with some epistemic power. The painting exemplifies the basic, everyday dynamic of human perception, the Gestaltist figure-ground relation through which we isolate a figure from a surrounding space in an act of intuitive awareness. The cut enables physical space—the white wall surrounding the lattice and the expanse opened up by the cutouts—to become significant in optical terms. In abstract art, blankness can effect a dialectical reversal: space that is “empty” becomes saturated with associations.

Much of twentieth-century geometric abstraction has been preoccupied with the implications of treating a painting as if it were an object in space, and Espinoza’s thematization of space occupancy is an extension of this modernist tradition. After all, we get access to space by moving through it, perceiving it. Consequently, notions of space in constructivist and minimalist sculpture are derived from painting, and geometric abstract art since Kazimir Malevich and Piet Mondrian has alluded to the qualities of sense perception (such as mass, volume, shape, positional relations of in front and behind) as “foci of attention for their own sake, rather than as factors encountered simply as aspects of our everyday practical dealings with the modern world.”

6

Paul Crowther, “Abstraction and Transperceptual Space,” in The Iconology of Abstraction: Non-Figurative Images and the Modern World, ed. Krešimir Purgar (New York and London: Routledge, 2020), 108–09. Generally, abstract art can be taken to allude to biological processes in nature, internal states, feelings, the workings of perception, or general states of mind. Crowther bases his notion of the transperceptual on Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s famous discussion of Paul Cézanne’s paintings and their ability to visualize the invisible in his 1964 “Eye and Mind” essay. See Maurice Merleau-Ponty, The Primacy of Perception, ed. James M. Edie, trans. Carleton Dallery (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1964.)

This author is indebted to Jesús Fuenmajor, who links Espinoza’s 1972 works to Merleau-Ponty’s writings on how Cezanne paints perception itself by foregrounding how figure-ground relations operate. See Jesús Fuenmajor, “Eugenio Espinoza: Unruly Supports (1970–1980),” in Unruly Supports, 22.

The abstract works in the constructivist tradition allude to space-formation as a mental, associative activity, and this provides an important gateway onto the subject matter of geometric abstraction.

7

For a lucid discussion on the seminal role of constructivism in Venezuelan art, see the writings of Luis Pérez-Oramas, including “Caracas, escena constructive,” 2020, https://tropicoabsoluto.com/2020/04/08/caracas-escena-constructiva/

More to the point, British philosopher Paul Crowther explains that all perception is transperceptual, built on complex mental processes of attention, selection, and association. “What we see is not a mere datum. Our recognition of it is based on its fitting with a horizon of visual expectations, constraints, and associations which are usually not noticed explicitly,” and, Crowther concludes, this comes to stand for the emergence of different “contextual spaces of expectation,”

8

Paul Crowther, Phenomenology of the Visual Arts (even the frame), (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2009), 108.

several of which can occur side by side in a single work of art. Frequently in Espinoza’s abstractions, the frustration of the viewer’s ability to see clearly, to see everything all at once, or to see with full certainty serves as a tactic to throw a wrench into automatic perceptual orientation, alluding to the transperceptual grounding of perception in mental processes.

9

In Espinoza’s Circunstantial (12 cocos) (1971) a grid canvas is suspended from the ceiling like a hammock, hiding from view a dozen coconuts placed inside it. Many canvases from the Museo de Bellas Artes show in 1972 do not reveal the physical causes for their deformation (such as sand tucked away by sewn canvas pockets). Espinoza’s well-known Impenetrable installation at the Ateneo de Caracas in 1972 featured a large grid canvas with a right-angle L shape that is placed about 30 inches above the floor as it reaches from wall to wall. Walking access is denied, and perceptual access is purposefully restrained by a single door so that it is not possible to see the full shape.

Simultaneously, another form of allusion is at play here, one which could be called a historical allusion. 10 Crowther makes note of the “phenomenological depth” of painting and its potential to foreground how the general structure of perception is subject to “contextual expectations.” This essay expands upon Crowther’s thinking to include a discussion of allusion as a literary and artistic device. An artwork previously perceived and studied can recede into the transperceptual background as a new contextual frame of reference. Espinoza’s Impenetrable installation from 1972 is based on an overt historical allusion to the playful, immersive, and participatory Penetrable installation by kinetic art pioneer Jesús Rafael Soto, exhibited at the Museo de Bellas Artes in 1971. The work is commonly read as an inversion, subversion, or critique of Soto’s work. See, for example, Juan Carlos Palenzuela, Arte en Venezuela: 1959-1979 (Caracas: Banco Mercantil, 2005), 153–56. As an artistic device of verbal and visual reference, allusions create more or less direct or indirect associations in a work of art to a place, event, person, or prior work of art. To allude to another work of art is not to depict (or imitate) it, but to refer to it by means of association. 11 Stephanie Ross, “Art and Allusion,” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism XXXX/1 (Fall 1981): 59–60. A non-literary visual-arts allusion is different from an adaptation, quotation, or citation. Ross cites as an example the Rouen cathedral series by Roy Lichtenstein which directly references Claude Monet’s series of cathedrals and yet transforms them into something new. This has an enriching function as the second artwork transforms the first, retaining it as a historical reference. 12 Sam Schwartz notes that “allusions are an essential tool for literary artists that often serve to situate their own works within the wider culture and the contexts of literary history.” See Sam Schwartz, “What is an Allusion,” Oregon State University, https://liberalarts.oregonstate.edu/wlf/what-allusion In psychology, mental association is a broad concept interpreted in general terms as a process in which a specific source is called upon by memory or imagination. Starting from perception and stemming from specific experience, in acts of association one image, object, or idea is linked to another, the latter coinciding with the former in one or more aspects of similarity, opposition, or contiguity. 13 For a basic definition of association in psychology, see Garima Pancha, “Association: Concept, Types, and Laws / Psychology,” https://www.psychologydiscussion.net/memory/association-concept-types-and-laws-psychology/1641. Pancha distinguishes between three different kinds of association connecting percept and ideas: association by similarity (through strong visual resemblance), by contrast (with a weak resemblance), and by contiguity (if B has always been perceived together with A, or immediately after it, then the perception of the idea of A will revive the idea of B).

Different idioms of geometric abstraction have explored different aspects of our perceptual and cognitive orientation toward the visible world on the basis of different historical and cultural circumstances unique to a region.

14

Cultural writer and anthropologist Néstor García Canclini brings this to a point when he writes that conventional linear temporality (which views postmodernity replacing modernity, which, in turn, replaces tradition) is undone when viewed from the perspective of Latin America. Instead, he argues for a “multitemporal heterogeneity” generated out of the contradictions between modernism and modernization endured with regional differences. Néstor García Canclini, “Modernity after Postmodernity,” in Beyond the Fantastic: Contemporary Art Criticism from Latin America, ed. Gerardo Mosquera (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1996), 28.

Art, in Canclini’s view, absorbs the conflictual structure of society, including its dependence on foreign models, aiming at a transformation of these structures from within the semiotic ability of art to communicate. Suffice it to say here that Espinoza’s position in this context requires further elaboration.

While it has generally been accepted that this era of modernist inquiry into the nature of experience has come to an end in U.S. and Europe in the 1960s, the practice of Espinoza productively complicates this timeline in its continued insistence on the phenomenological depth of painting as a gateway onto the allusive nature of the mind. Espinoza’s canvases, we might conclude, explore the full potential of the allusive nature of abstraction by opening contextual spaces of expectation beyond the transperceptual.

15

Not finding any of the established 1960s Venezuelan traditions of informalist, kinetic, or optical abstraction rewarding, Espinoza began looking toward the wider history of art. To find a way out of established traditions of Latin American art (kineticism, magic realism, figuration), Espinoza visited the library at the Museo de Bellas Artes frequently in the late 1960s to look at art books and journals. Miguel Arroyo, then director of the museum, was known for his internationalist exhibition program featuring movements such as pop art, arte povera, minimalism, and postminimalism during the mid to late 1960s. Clara Diament Sujo, director of the art gallery Estudio Actual (founded in 1968), frequently traveled to New York, bringing Artforum and other U.S. magazines back. Espinoza mentions that he had access to Artforum for visual stimulation but did not read the English language content. Phone interview with the artist, May 10, 2022.

In Onceptual #9, black canvas strips dangle down freely from selected cells, many of which reach into the space below the bottom of the grid. (Figure 3)

Two things are especially noteworthy in Onceptual #9. First, we encounter a jarring discrepancy between what we see and what is physically there that jeopardizes a viewing experience of perceptual automation. Measuring 48 by 73 inches, Onceptual #9 is, in fact, a rectangle. To the naked eye, however, its shape appears to be that of a square. This contradiction between the numerical information of the “real” canvas size and what we perceive it to be, yet again, alludes to the transperceptual nature of perception as a set of mental operations. This instance refers us to how perception is grounded in the biological workings of the human mind. In the context of the Gestalist rules of psychology, size is an absolute value that can be measured, but shape is contingent on perception. Second, Onceptual #9 presents a conscious formal variation of a canvas from 1971, exhibited at the artist’s 20 Obras recientes solo show at the Museo de Bellas Artes in Caracas in the summer of 1972. (Figure 4)

By comparing the two canvases, we process similarities and differences. The more recent work alludes to the earlier one. 16 For self-reference as a form of literary allusion, see MasterClass, “What is Allusion in Writing? Learn About the 6 Different Types of Literary Allusions and Neil Gaiman’s Tips for Using Allusion in Writing,” 2022, https://www.masterclass.com/articles/what-is-allusion-in-writing-learn-about-the-6-different-types-of-literary-allusions-and-neil-gaimans-tips-for-using-allusion-in-writing Both paintings feature a lattice structure of eight noticeably vacant squares held together by a single white rectangle in the center. Self-reference (considered a special form of historical allusion) has been elevated by Espinoza to a point of method since the 1970s. Critic Ruth Auerbach specifically noted that “the appropriation of his own work, shifting time and place, is perhaps Espinoza’s most determined and conceptual undertaking.” 17 Ruth Auerbach, “Eugenio Espinoza: Shifting Geometries: A Chronological Approach to Pictorial Obsession,” in 3 Perspectives: Eugenio Espinoza/Álvaro Oyarzún/José Alejandro Restrepo (Miami: Cisneros Fontanals Art Foundation, 2007), 21. Rather than considering permutational variation in painting an act of appropriation, like Auerbach suggests, we might consider it a form of reference in which a work is given a new body, selectively alluding to the former work by taking over some formal parameters while varying others. The historic work from 1971 features a wooden bar at the top and one at the bottom to provide structural stability: the bunching of the soft fabric canvas that wraps around the hard support creates vertical wave-like sagging that affects the entire inner compositional order. This is very unlike the soft, sagging shape of Onceptual #9, mostly caused by a method of suspension from four equidistant hooks. Whereas the canvases from the 1970s feature a more or less solid, weighty physicality, space occupancy in the contemporary Onceptuales series impresses itself upon us no less viscerally as an equilibrium of opposing forces arrested in motion: absence and presence, balance and virtual motion, gravity and the suspension of it animate the works from within.

In Onceptual #010 and #72, fabric even more forcefully collapses in on itself by the force of its own weight, gravity, and the laws of nature in general. Instead of identical square cells forming a grid, these felt works feature two rectangular rows that sit atop each other. Reinforced by the cast shadows, a curvilinear pattern of sorts moves from left to right. (Figure 5)

The artist has bent shapes by hand into wave-like undulations. Simultaneously, motion is implied virtually as an optical effect that exists only in the viewer’s eye-brain response. The hooks themselves are form-giving and have become figure as many are freed from their function as the primary tools of suspension. The dependence on the nail, and the subsequent gravity-bound deformation of the material, is reminiscent of American process art, albeit only superficially.

In American process art of the late 1960s and early 1970s, the gestural activities that form the sculptural material during production are not hidden but remain a prominent element of the final work. The idea of foregrounding the process of making—with the appearance of the work as the joint result of the artist’s activity, the type and physical behavior of the materials employed, and the choice of display method—is said to have been initiated by the drip paintings of Jackson Pollock in the early 1950s. Shifting process art into the format of sculpture in the late 1960s, postminimalist artist Robert Morris made long cuts into rectangular pieces of industrial felt, hanging them from a nail. This allows gravity and the innate properties of the material to partake in shaping the work of art. Pollock’s point was that, rather than depict a figure, the irrational forces of the psyche alongside the rhythmic movements of the body leave gravity-bound traces on the canvas, bringing him in sync with nature. Echoing an emphasis in American art on nature as a form-giving and destabilizing force, Espinoza asserts the primary importance of “being close to the laws of gravity, stones, and other elements.” 18 Eugenio Espinoza: Retro/retrospectiva 2016-1973 (Tenerife: Fundación Saludarte and Wecksler Publishing, 2017), 21. In a clear deviation from a nature-bound aesthetic, we encounter a geographically-specific reflection on the tension between rural and urban life in the metropolitan city of Caracas under modernization. 19 We might read Espinoza’s project as a reintegration of nature into city life and order that functions simultaneously as a territorial rebalancing. Historian John W. Lombardi concludes that “the close connection between man and land in the Venezuelan context” has been “weakened by the dissolving power of technology and wealth” almost exclusively concentrated in the political and economic capital of Caracas since the mid-eighteenth century. John W. Lombardi, Venezuela: The Search for Order: The Dream of Progress (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982), 8, 10. Espinoza’s strategy, as it has been developed since the early 1970s, has been to explore the artist’s space-bound state as a way to deform a figure (in his case, the square order of simple geometry) by harnessing the gestural activities of the hand in tandem with both industrial and tropical materials such as sand, coconuts, or palm. (Venezuela is bound by the Caribbean Sea to the north.) Born in San Juan de los Morros situated in the southern slopes of the mountainous central highlands, Espinoza came to Caracas late in 1966 as a young adult to attend the Escuela de Artes Plásticas Cristóbal Rojas. His rural upbringing shaped his physical response to the city, compelling him to seek out the natural in all existence.

In Espinoza’s practice—not unlike in the Italian arte povera project, which was received well in Venezuela—nature is brought into art not in a pure but in a broadened sense, now conceived of as that which comprises the three-dimensional world and the micro and macro processes that govern both organic and industrial city reality. 20 See Laura Petican, “The Arte Povera Experience,” in Meanings of Abstract Art: Between Nature and Theory, ed. Paul Crowther and Isabel Wünsche (London and New York: Taylor & Francis, 2012), 185–86. Unlike in arte povera’s literalist use of nature, in Espinoza’s work natural materials enter into an ever so complex web of associative reference that insists on the cultural specificity of the local and the mental contingencies of space perception. Importantly, Espinoza implicates the observer of art into a dynamic process of subjective experience. Onceptual #010 and #72 also solicit virtual movement in the local tradition of optical art pervasive in the Venezuelan scene of the 1960s. Allusions, after all, tend to occur in bundles, but with different contextual spaces of expectation associated with them: allusions to the transperceptual grounding of perception in Gestaltist psychology, self-reference, and visual and verbal allusions to the history of art, among other realms. 21 Supported by artist statements linking the grid to urban and social order, the ever-growing literature tends to interpret the deformed grid canvas as a metaphor for the failure of modernist architectural and urban renewal politics in Caracas associated with the public building projects of architect Carlos Raúl Villanueva for the Universidad central de Venezuela. This reading takes the canvases’ dialectical appearance of order and deformation, structure and chaos, as structurally homologous to the internal historical contradictions of modernization in Venezuela in the 1950s and 1960s. This standard reading of Espinoza’s work as a critique of Venezuelan urban and architectural modernization under the influence of international style art, geometric universalism, kinetic playfulness, and optical dematerialization, however, stands to be reevaluated in the context of a wider network of allusion to the grid in multiple historical and disciplinary contexts, including the history of art.

The title of the series, Onceptuales, is hard to pronounce, almost concretist in sound quality. A strategy of perceptual disorientation also works in the context of language. It is impossible to make sense of its meaning unless we understand the word “onceptual” as a verbal allusion to a different historical context, slashing the letter c of the term conceptual, as in conceptual art. Conceptual art is a multi-faceted Anglophone invention. Given Espinoza’s proclivity for working with the simple geometry of the square in space, we might look toward the writings of Sol LeWitt to interpret this historical allusion.

In his 1966 text “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art,” LeWitt famously wrote that the idea or concept is the most important part of a work of art whose execution is of secondary importance, since everything is planned beforehand. 22 Sol LeWitt, “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art,” Artforum , no. 10 (Summer 1967), https://www.artforum.com/print/196706/paragraphs-on-conceptual-art-36719 He adds that the idea in art does not need to be complex, but rather thrives on simplicity. Gestural activity is key in Espinoza’s work, and the “idea” is not readily accessible, but rather requires a heavy interpretive effort. And yet the verbal allusion to conceptualism has meaning, as it thematizes in the most general terms how the perceptual and the conceptual as singled out properties of a work of art are brought into new kinds of alignment. Despite the many differences between LeWitt and Espinoza, this overt historical allusion engages us in a string of thoughts on how Espinoza’s abstractions are “conceptual.” 23 Juan Ledezma employs the writings of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari on the relation between sense and concept to grasp Espinoza’s rethinking of painting in the context of a realignment of the perceptual and conceptual in art. Painting, Ledezma rightly notes, cannot be conceptual. In the experience of its physical appearance and formal makeup, however, new concepts as “nomadic territories” can emerge in the response of the viewer. Juan Ledezma, “Painting as Event,” in Unruly Supports, 95-99. Long before Espinoza’s overt titling of the Onceptuales series, critics and artists have queried his work’s conceptual nature, starting in the late 1970s. To take one case in point, fellow Venezuelan artist Claudio Perna, arguably the artist of his generation who employs conceptual idioms in the most readily discernible way, stated retroactively in the 1990s that he thinks that “Eugenio Espinoza is one the great conceptual artists.” 24 Eduardo Costa, “Beyond Geometry, Conceptualism and Earth Art,” Arte al Día International, no. 108 (2005): 18.

By shifting the plastic device of the cut into the realm of language, Espinoza opens Pandora’s box: questioning what conceptual art is, how it has been received in Latin America under the label of conceptualism, how an entire generation of Venezuelan artists in the 1970s has or has not defined itself as conceptual, and how the recent literature has come to assess what Venezuelan conceptualism stands for. The work also prompts a final, broader question: is there even such a thing as a conceptual painting? This author will not go down that rabbit hole, at least not in this text, as this discussion deserves some serious attention beyond the scope of this essay. The answer to the question of the work’s conceptual nature, however, shall not completely be sidelined in this text either. The answer depends on how we define what conceptual art is, how conceptualism in Latin America operates in similar and different ways to the Anglophone movement, and how we account for regional differences between different countries in the Southern Hemisphere. This line of questioning is indicative of how Espinoza’s allusive art repeatedly forces us to think about the intellectual presuppositions behind both the percepts and concepts of our understanding of art (and everyday life in general.)

In discussions of Venezuelan art of the 1970s, much of the art that falls between genre and media boundaries—in the absence of a better style or movement term—has been referred to as conceptual art, keeping the definition of Venezuelan conceptualism broad. 25 Blanco, “Recordando sin iras (Remembering Without Rancor),” 10. She notes that when genres are abolished, instability and chance become new paradigms. Following Blanco’s discussion, Manuel Ortega Navarro defines conceptual art in Venezuela in the broadest terms possible as “all art is conceptual, understanding that the plastic arts are not based only on pure visuality. Art is made by the human being and as such, has sensations, memories, prejudices, etc., that produce in the artistic work a result of his personal interpretation.” See Manuel Ortega Navarro, “Origen del arte conceptual en Venezuela,” SituArte: Revista arbitrada de la Facultad de Arte de la Universidad del Zulia (año 1, no. 2, enero – junio 2007), 68, https://produccioncientificaluz.org/index.php/situarte/article/viewFile/15940/15913 The more forcefully the cut solicits the associative power of “empty” space in the Onceptuales series, the closer the wall-hung work moves toward the format of sculpture, in the process posing what defines each medium as a question. Since Onceptual #010 and #72 are fashioned from industrial black felt, color is disconnected here from paint and the activity of painting. The question of a work’s ontological status emerges into view here. These two Onceptuales works only evoke the idea of painting by harnessing selected conventions associated with that medium, such as wall-hanging a rectangular item. Technically (factually), the work is a sculpture.

To paraphrase the father of conceptual art, Marcel Duchamp, and his famous question of how you can make art without making art, Espinoza shifts the discussion into the realm of media, asking, “How can you make a painting without painting it?” Espinoza arrived at an anti-formalist reading of media, favoring a semiotic-communicative notion of art as a bundle of choices, by studying the work of Venezuelan wire sculptor Gego. In an eight-page text written on the occasion of Gego’s Drawings without Paper exhibition in 1986, Espinoza observes, “I understood everything immediately, when I saw that the ‘drawings’ [made from twisting wire into shape] did not occupy a sculptural space but the frontal space of the wall, like a hung painting. But they were really drawings; they were ‘truly real’ lines, you could touch them, and they were there to create a number of cleverly constructed spatial relationships.” 26 Eugenio Espinoza, “On Gego,” in: Gego: Dibujos sin papel (Barquisimieto: Museo de Barquisimieto, 1985), n.p. By isolating a material, a single technique, or a medium-specific formal convention from one art format and introducing it into another format in an act of translation (based on an analogical linkage), the conceptual boundaries between media begin to fluctuate.

The art-historical assessment of what marks Venezuelan conceptualism is currently underway. The discussions tend to share a broad definition of this term to accommodate the wide range of divergent practices in the 1970s under one umbrella, ranging from an aforementioned dissolution of media-specific boundaries, to an intensified participation in art (by means of hands-on activities or a more open mental effort of making meaning), to an increased reliance on performance and performative measures. 27 Miami-based critic Félix Suazo follows the contemporary writings of María Elena Ramos from 1981, informed by a McLuhanesque notion of communication, to argue that any artwork that demonstrates “an explicit interest in the presence, participation and relationship with the viewer” as a vital element in the process of codifying and interpreting the work could be deemed conceptual. See Félix Suazo, “Prácticas conceptuales y micropolitíca del signo en Venezuela,” Revista Kaypunku:: Revista de Estudios Interdisciplinarios del Arte, Diseño y la Cultura (December 2014): 140-141. In an essay first published in 2008, Venezuelan scholar Gabriela Rangel employed Mexican-based Peruvian art critic Juan Acha’s 1981 notion of “non-objectual art” to designate the 1970s turn toward hybrid and ephemeral art as one in which the body of the artist creates situations and performance as conceptual. Gabriela Rangel, “An Art of Nooks: Notes on Non-Objectual Experiences in Venezuela,” Hemispheric Institute of Performance and Politics, 2021, https://hemisphericinstitute.org/en/emisferica-81/8-1-essays/an-art-of-nooks-notes-on-non-objectual-experiences-in-venezuela.html Espinoza can indeed be considered a key practitioner of Venezuelan conceptualism as his work subscribes to each of the defining characteristics currently at play in the critical literature. This kind of categorical attribution can be useful, but only if it does not overshadow the specific nature of an individual practice.

What stands out in Espinoza’s practice is a dual emphasis on the phenomenological depth of painting and the allusive nature of abstraction as a biologically anchored and culturally contingent field of expectations, where one serves as a platform onto the other. One of the lessons to be learned here is that looking closer at what is actually there always functions as a gateway into thinking deeper.